RICHARD NATKIEL

ATLAS OF WORLD WAR II

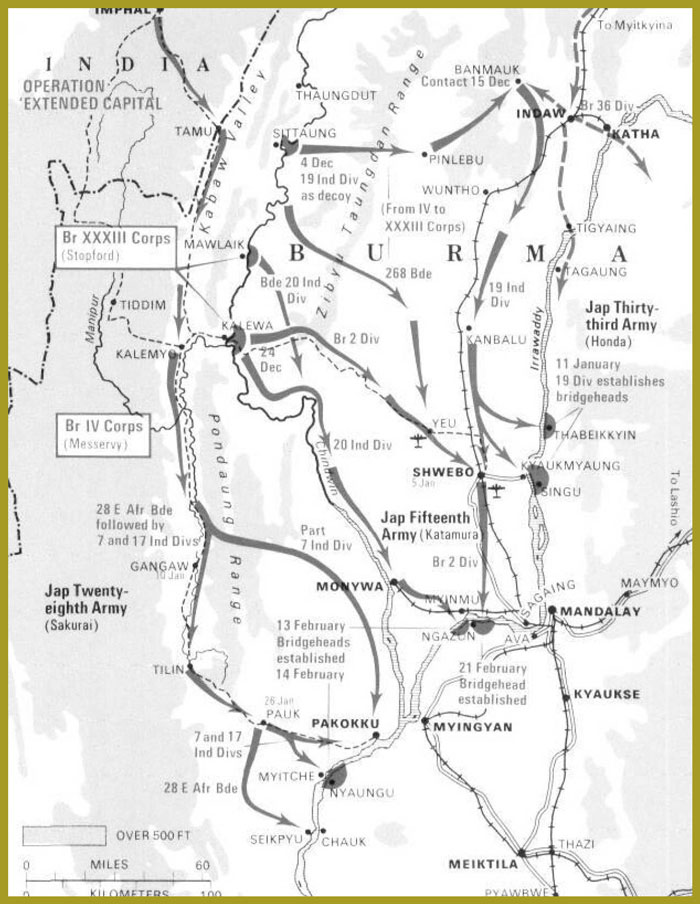

Operation Extended Capital took the Allies across the Chindwin and on to Mandalay.

Flamethrower and rifle-equipped infantry of the United States Army prepare for action.

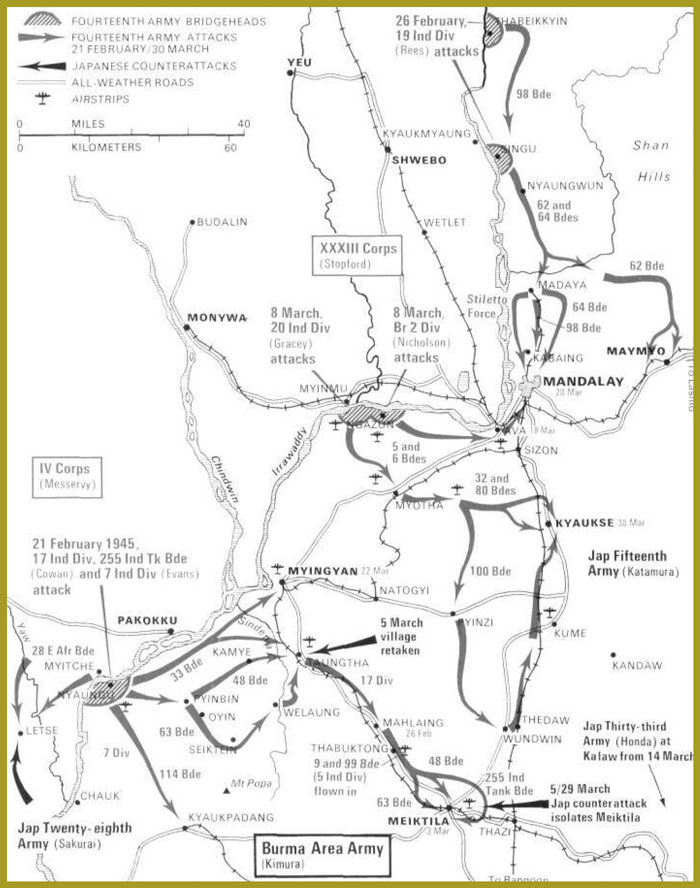

Control of Meiktila was to prove of crucial importance in the battle for Mandalay.

US troops pause on a Burmese jungle trail.

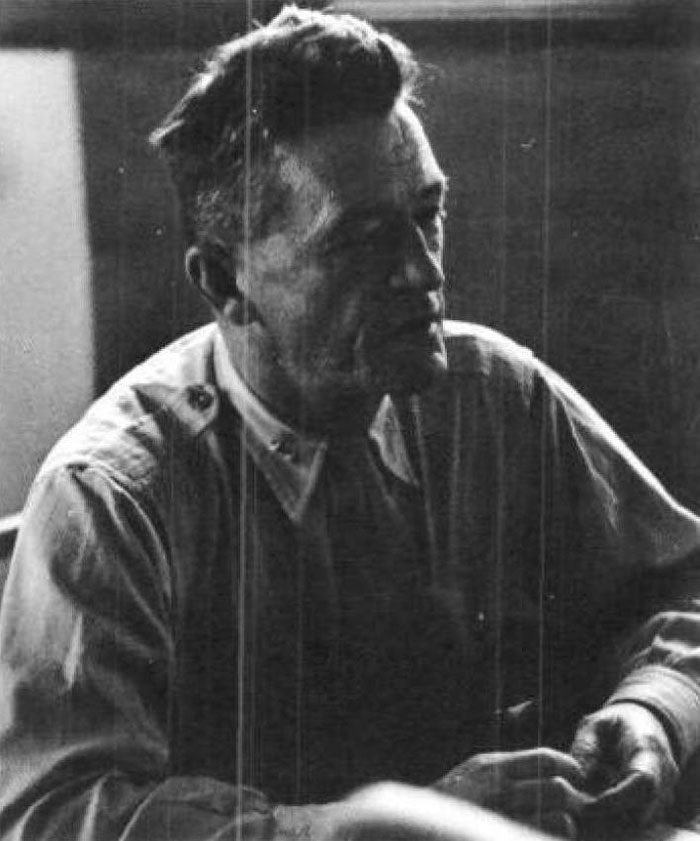

General Claire Chennault, whose 'Flying Tigers' struck at Japanese ground troops in China and Formosa.

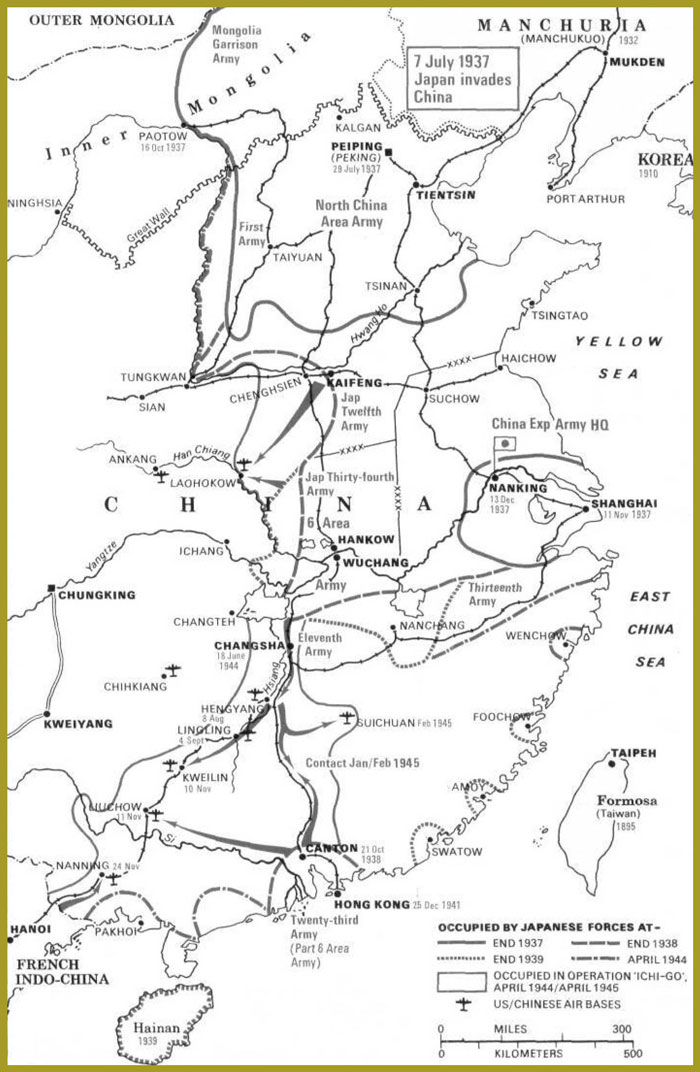

China's struggle to repel the Japanese invaders.

Japan's war on China predated World War II by several years, and by 1939 the aggressive island empire had seized control of China's richest areas. The 'sleeping giant' was especially vulnerable on account of the internal strife between the Nationalists (or Kuomintang) led by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Tse-tung's Communists.

US General George C Marshall warned the Allies that Nationalist China must be propped up; otherwise, the Japanese Government could flee to China when the home islands were invaded - as was then planned - 'and continue the war on a great and rich land mass.' Throughout the war, the US shipped enormous quantities of supplies to China, first by the Burma Road, and after 1942 by air over the Himalayas - a dangerous route known as 'the Hump.' Chiang's position was strengthened by the creation of the US 14th Air Force, impressively commanded by Brigadier General Claire Chennault, which inflicted heavy damage on Japanese troops both in China and Formosa. General Joseph 'Vinegar Joe' Stilwell was sent in to help retrain the Chinese Army. However, many of the supplies destined for use against the Japanese were diverted into Chiang's war on the Communists; corruption flourished in his Nationalist Party.

US air strikes by Chennault's 'Flying Tigers' provoked a Japanese offensive against the airfields at Liuchow, Kweilin, Lingling and other sites in the spring of 1944. Chinese resistance did not hold up, as was often the case, and the loss of these bases hampered Allied operations until December. Meanwhile, a truce was patched up between the Communists and Nationalists, allowing greater activity against the Japanese, who renewed their offensive in 1945.

In the war's final year, Japanese General Okamura overextended the deployment of his China Expeditionary Army, and the Chinese were able to cut off the corridor to Indochina. They held this position for the duration, after which the Nationalists and the Communists promptly resumed their civil war.

Red Army sappers clear German barbed wire defenses.

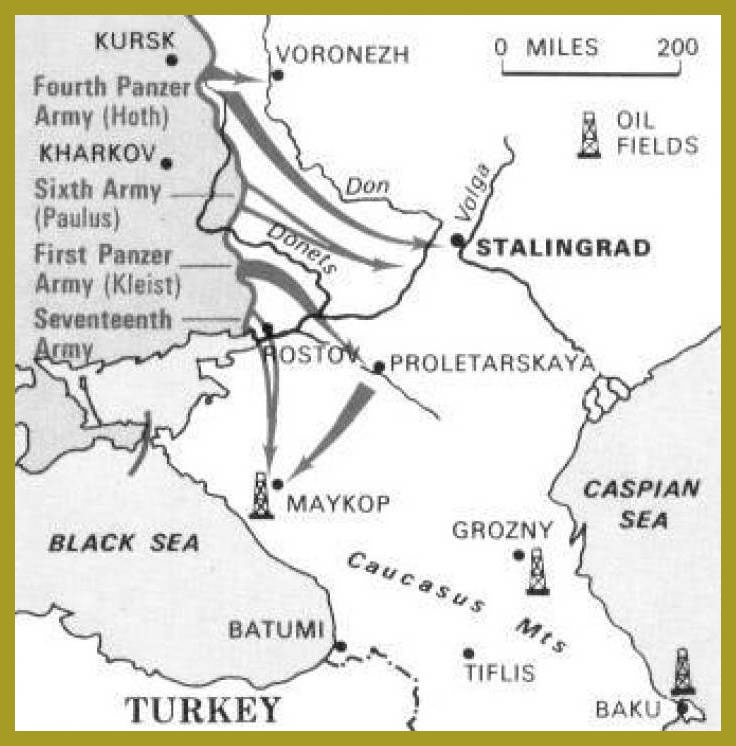

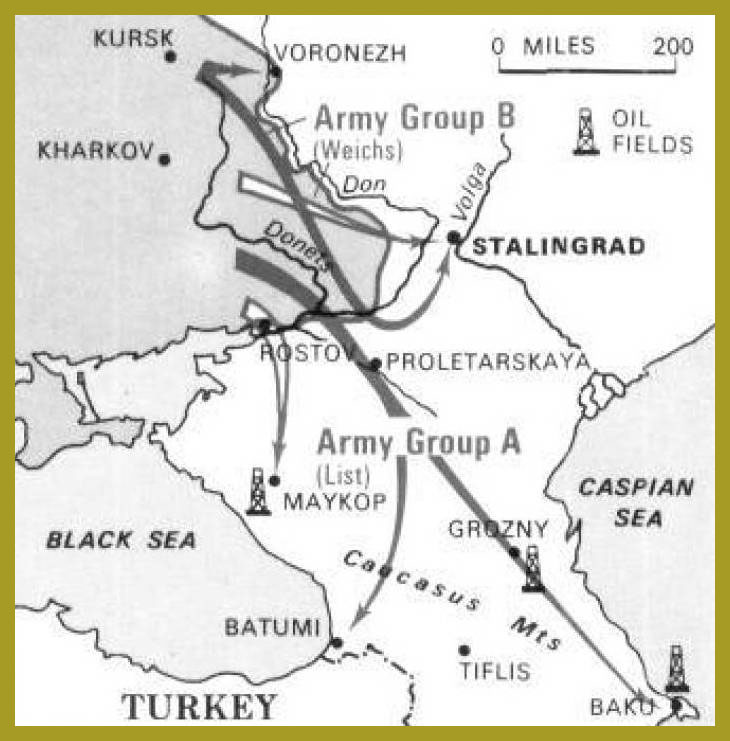

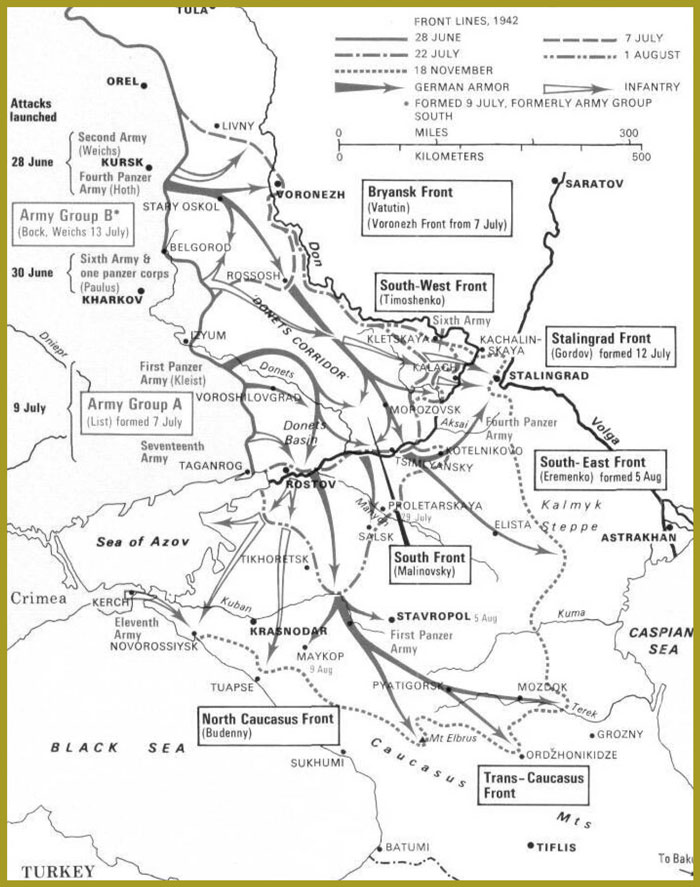

Germany's critical oil shortage was decisive in Hitler's first 1942 campaign plan for the Eastern Front. In April he instructed that the main effort was to be in southern Russia, where German forces must defeat the Red Army on the River Don and advance to the coveted Caucasian oil fields. For this campaign, Bock's Army Group South was reorganized into Army Groups A and B, A to undertake the Caucasus offensive and B to establish a protective front along the Don and go on to Stalingrad. The neutralization of 'Stalin's City' soon gained a compelling hold on Hitler's mind, despite his staffs objections to dividing the German effort before the Red Army had been shattered. Stalingrad was a major rail and river center, whose tank and armaments factories offered additional inducements to attack it.

The obsession with Stalingrad was a disastrous mistake on Hitler's part, compounded by his seizure of control from his dissenting officers. Army Group A made a rapid advance from 28 June to 29 July, capturing Novorossiysk and threatening the Russian Trans-Caucasus Front. But the diversion of 300,000 German troops to the Stalingrad offensive prevented them from achieving their original objective - the Batumi-Baku Line. They were left to hold a 500-mile Caucasian front against strong Russian opposition - leaderless, except for the erratic and contradictory orders of Hitler himself.

The Russians had made good their 1941 manpower losses from the subject peoples of Asia, and they threw the T-34 tank into the field at this point to complete the German fiasco in the Caucasus. The vital oil fields were lost to Germany. Army Group B raced toward Stalingrad to attempt what had now become the only possible success of the campaign. The city could not be encircled without crossing the Volga, which General Weichs lacked the resources to attempt, so a frontal assault was launched on 31 August.

The original German battle plan, with oilfields the main objective.

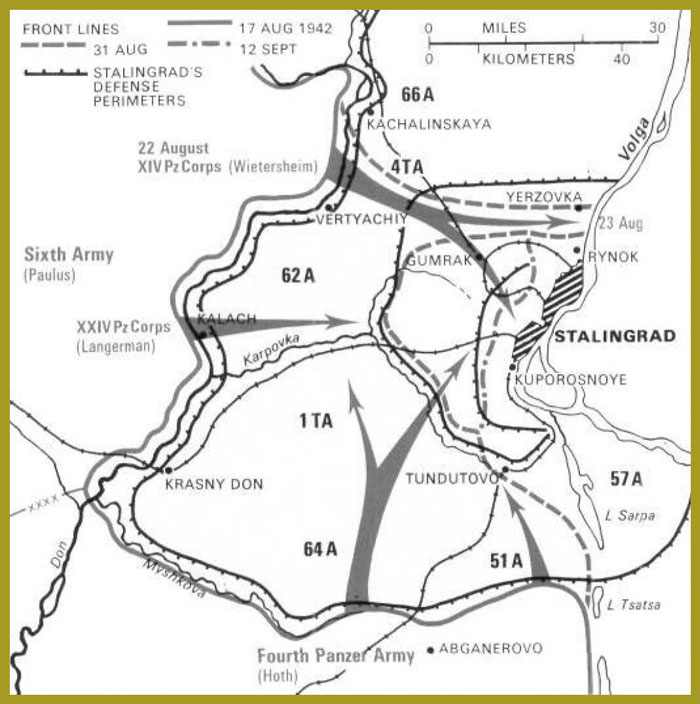

Splitting the forces to strengthen the attack on Stalingrad proved a major error.

The German advance south-eastwards with armor and artillery.

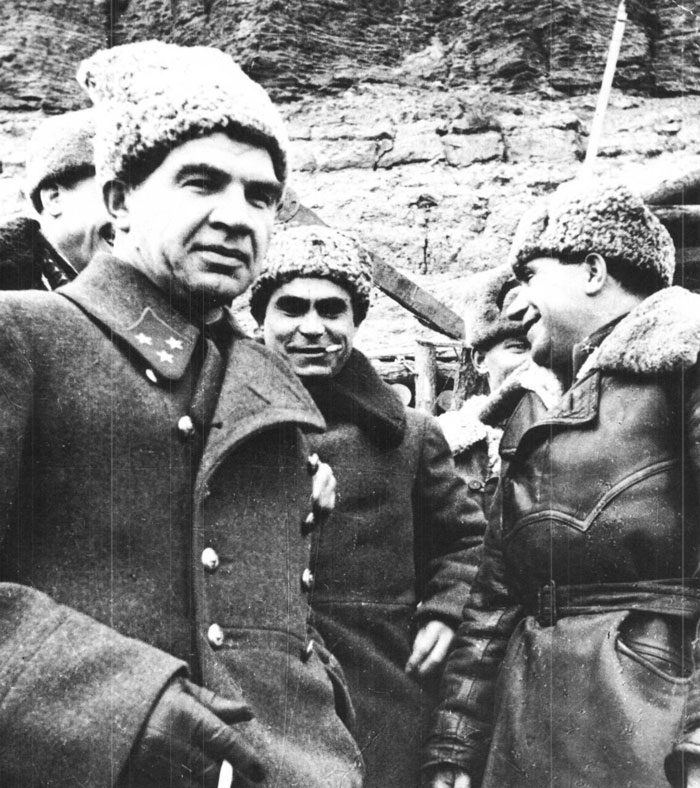

Commander Chuikov of the Russian 62nd Army at the Volga.

The slow pace of the German summer offensive of 1942 allowed Stalingrad's defenders to strengthen their position considerably. The city was home to half a million Russians, who were united in their determination to repel the German assault. Most of the Soviet soldiers were assigned to the defense perimeter, the city itself being entrusted largely to armed civilians, whose high morale promised fierce resistance.

The Volga wound through many channels around the city, posing serious obstacles to any attempt at bridging it. The Germans made no effort to establish a bridgehead north of the city so as to block river traffic and reinforcement.

The German forces attack.

Stalingrad's position on the banks of the Volga enhanced its defensive capabilities.

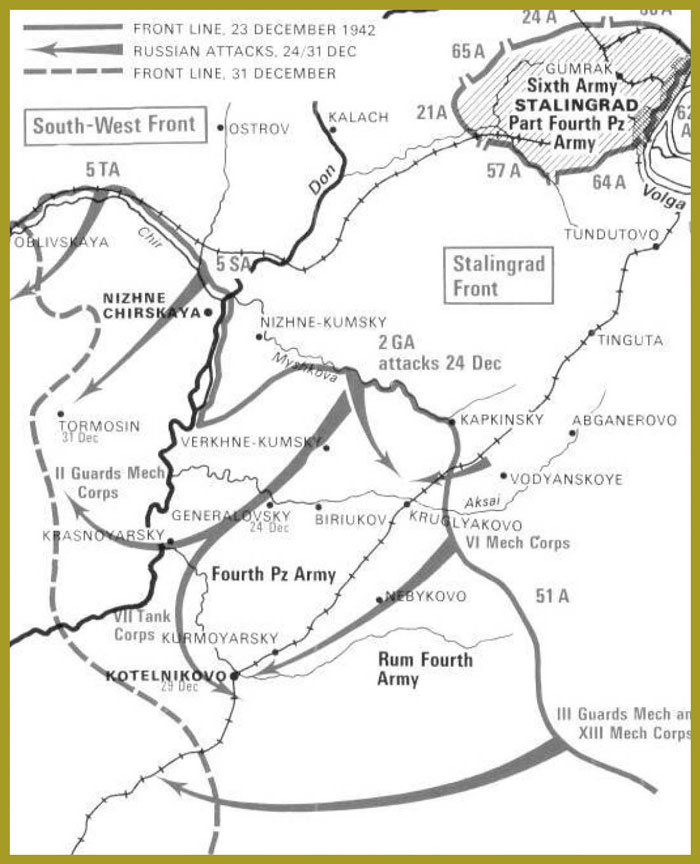

Manstein's forces are repulsed.

A German soldier shows the strain of fighting an unwinnable battle.

The red flag flies victorious over Stalingrad in February 1943 as the Germans finally surrender.

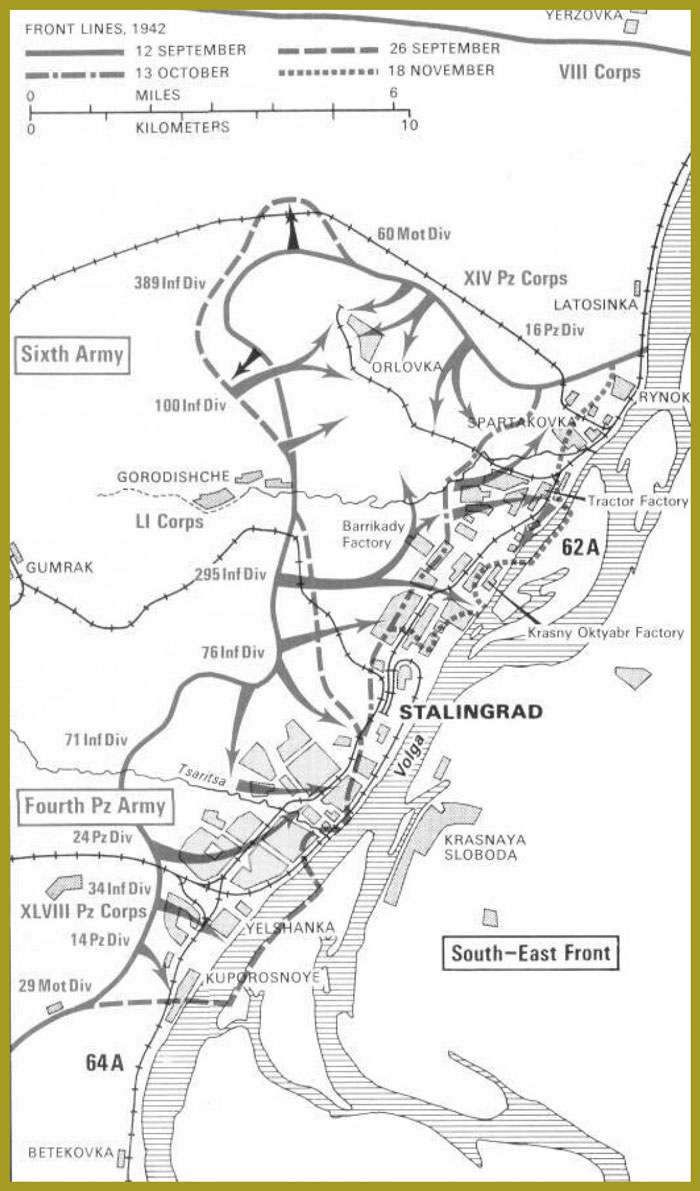

This was only one of many mistakes, the worst of which was the decision to carry the city by direct attack. The resultant battle would become the Verdun of World War II.

By the end of August, the Russian defenders had been squeezed into a small perimeter, and twelve days later the Germans were in the city, striving to fight their way to the western bank of the Volga. Soviet civilians and soldiers struggled side by side in a constant barrage of bombs and artillery fire, falling back a foot at a time. House-to-house fighting raged until 13 October, when the exhausted German infantry reached the river in the south city. But the northern industrial sector remained unconquered. Hitler ordered intensified bombardments that served only to make the infantry's task more difficult. Stalingrad's defenders continued to fight regardless.

By 18 November, when the winter freeze was imminent, Hitler's armies around Stalingrad were undersupplied, overextended and vulnerable to the Russian counterattack that was forming. Before the Germans were forced to surrender (February 1943), they had lost 100,000 of the 200,000 men involved. Five hundred Luftwaffe transport planes had been destroyed in impotent efforts to supply them, and six months' worth of German war production had been thrown away. Wehrmacht morale was shattered, not only by the great defeat itself, but by the wanton intrusions into military planning that had wrecked the campaign from Berlin.

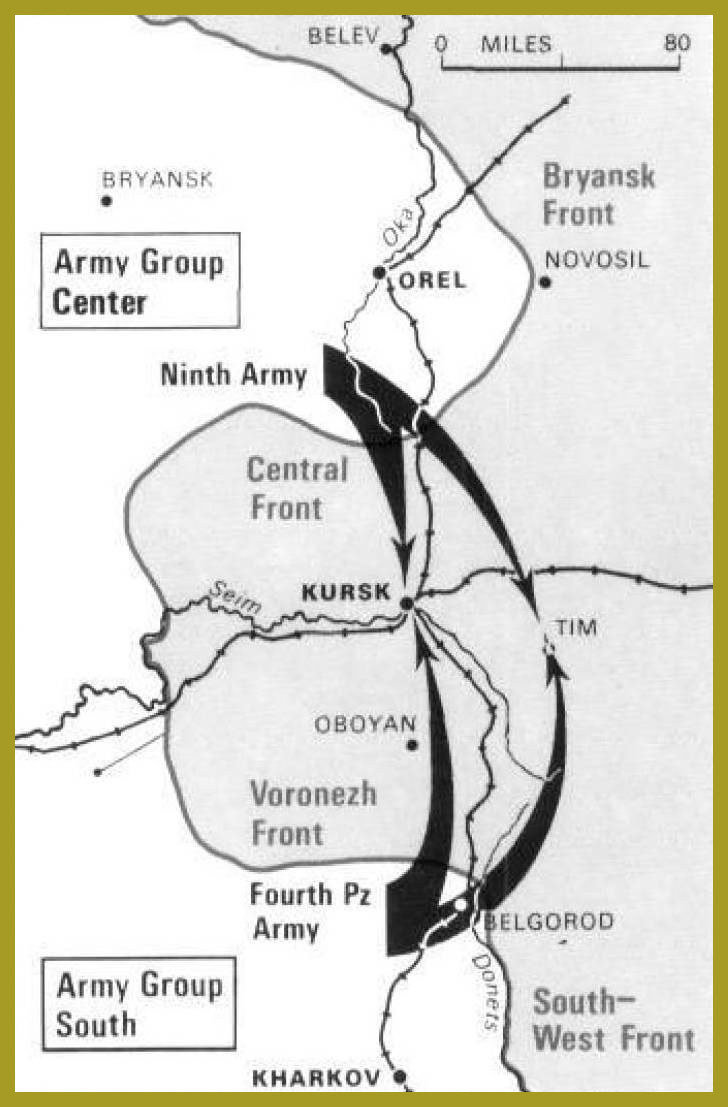

The success of the 1942 Russian winter offensive left a large salient around Kursk that tempted the German High Command into mounting a major attack. The fact that US and British aid was now flowing freely into Russia lent urgency to this plan of attack, as Germany's resources were steadily draining away.

The armored pincer movement against the Kursk Salient - codenamed Operation Citadel - was scheduled for July of 1943. Early intelligence of it enabled the Russians to prepare by moving in two armies and setting up eight concentric circles of defense. When the Germans launched their attack on 5 July, it was in the belief that they would achieve surprise. On the contrary, Russian defenses at Kursk were the most formidable they had ever assaulted. The Soviet T-34 tank was superior to anything the German Panzer groups could field, and air command was seized at the outset by multitudes of Russian planes. They were not equal to the Luftwaffe in technology, but they were far superior in numbers.

The German offensive against Kursk, launched on 5 July.

By 20 July German forces were in full retreat.

The heavily armored KV-1 tanks gave the Germans many problems.

Soviet T-34s take part in the biggest tank battle of the war near Prokhorovka in the south.

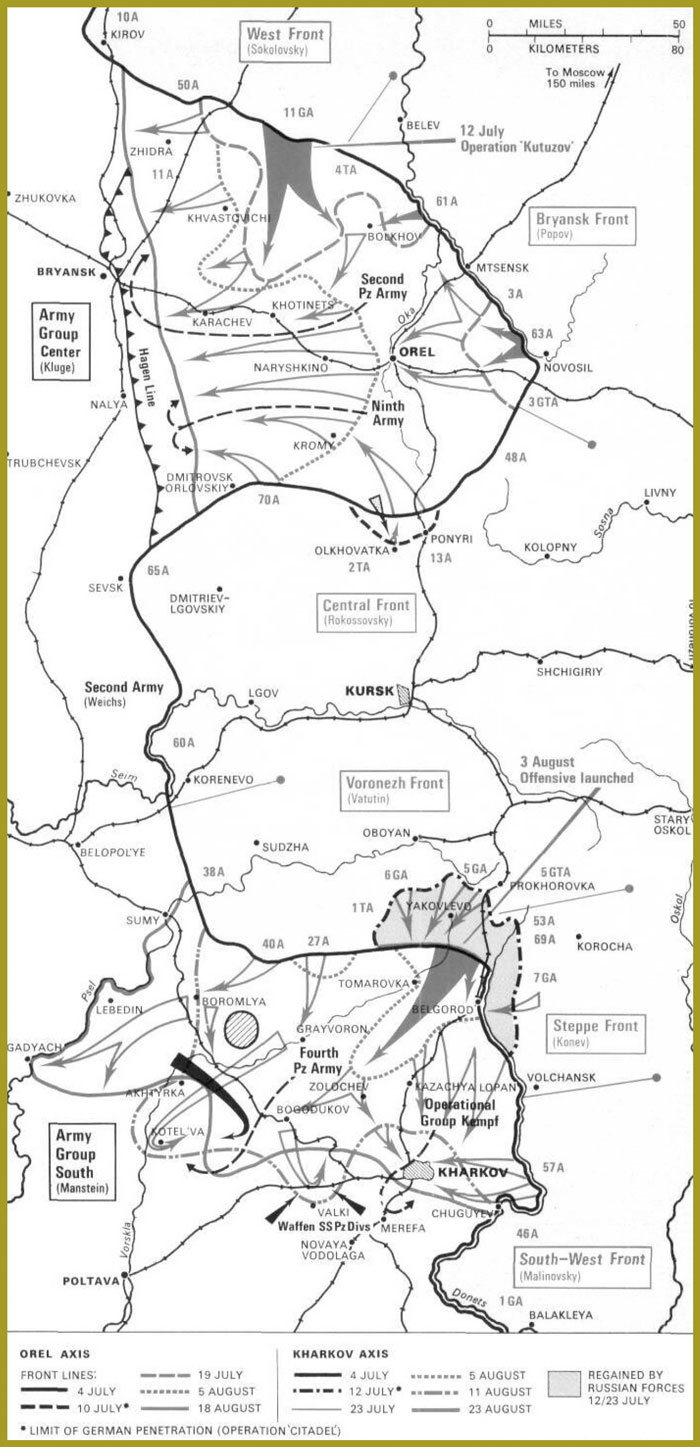

In the north, German Ninth Army advanced only six miles in the first few days, at a cost of 25,000 killed and 400 tanks and aircraft. In the south, Man- stein's Fourth Panzer Army drove through the Russian Sixth Army - again at high cost - only to face fresh Soviet tank units from the Russian Steppe Front reserve. The largest tank armies in history clashed near Prokhorovka on 12 July and fought for seven days. Initial German success was followed by increasing Soviet ascendancy, and by 20 July all German forces were in full retreat. Two million men had been involved, with 6000 tanks and 4000 aircraft. Many of the surviving German tanks were dispatched immediately to Italy to counter the Allied offensive that had begun with landings in Sicily. The Russians maintained their momentum in successful advances south of Moscow.

By fall of 1943, the Soviets had pushed their front line far to the west against diminishing German forces that managed to stay intact and resist, although they could not prevail. In mid September the Russians threatened Smolensk in the north and Kiev in the center. They crossed the Donets in the south and by 30 September had captured Smolensk and established themselves along most of the Dniepr.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com