IAN BAXTER

IMAGES OF WAR. Hitler's Mountain Troops. The Gebirsjäger. Rare Photographs from Wartime Archives

Two mountain troop motorcyclists can be seen with their BMW motorcycles in a stream, cleaning their dusty vehicles. By this period of the war, many of the motorcyclists were used for dispatch purposes to various sections of the front, and because motorcycles were regarded as versatile machines, it enabled them to move swiftly across terrain with important information.

Two troop leaders can be seen halted on a road with their unit. The troop leader, wearing his M35 steel helmet and 6×30 field binoculars, wears the 1st pattern MP38/40 magazine pouches for his MP38/40 sub-machine gun. By 1941, the MP38/40 sub¬machine gun was manufactured in great numbers, and issued to squad leaders, senior NCOs and front line officers.

A Gebirgs FlaK 30 gun in an elevated position. The guns usual shield has been removed, probably to lighten the weight. Normally, the shields were used when the gun was being utilized against a ground target.

A group of mountain troops push a sanitation vehicle up a steep gradient. It is unlikely that any of these men are part of the medical personnel, except one seen wearing a white overall. Normally, all medical aide-men wore the Red Cross on a white armband.

Out in a field and the crew of a 7.5cm GebG36 are seen poised in a field with their gun in an elevated position. Note, the Gebirgs crew wearing the silver Jäger cap badge of three oak leaves and an acorn as worn by Jäger-Divisions.

Three photographs showing a Gebirsjäger taking aim with his carbine 98K bolt action rifle. He wears the camouflage wind jacket which was similar in design to that of the Waffen-SS camouflage smock. It was made of waterproof fabric, and he is seen here wearing white-side out. The other side of the jacket was printed in three colours, similar to that of the Wehrmacht splinter jacket.

Five photographs showing Gebirgs troops during operations on the Ostfront. As with many Gebirsjäger units during winter operations, they are using animal draught to tow sleds full of supplies. Although the Gebirsjäger continued to fight hard to hold their positions, they were constantly subject to intense bombardments by whole divisions of Soviet artillery. Difficulties of terrain, too, hindered communications between the units, especially in the snow. One of the quickest and effective methods of moving from one part of the front to another was either by ski or sled.

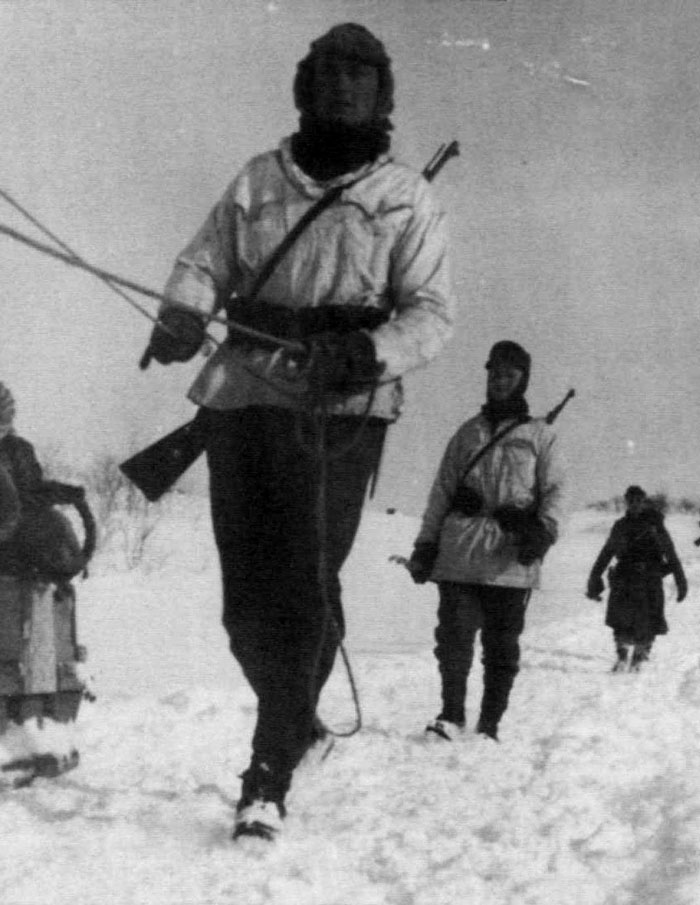

A ski patrol can be seen moving towards some high-ground. Shelter for the soldiers was often at a premium, especially when evacuating a position. Quite frequently, out in the snow, soldiers were compelled not only to build various forms of shelter to combat the arctic temperatures, but to protect themselves against enemy fire.

Two commanders scrutinize a map during defensive operations in Army Group South. The officer on the right is wearing another variety of animal skin fur coat. His comrade wears the familiar white camouflage smock and can clearly be seen wearing the coloured friend-or-foe recognition stripe on his sleeve.

A snow ski patrol prepares to leave camp. The two ski soldiers nearest to the camera are wearing the shapeless two-piece snowsuit comprising of a snow jacket and matching trousers. The jacket was buttoned all the way down the front with white painted buttons. It had a large white hood, which could easily be pulled over the steel helmet. The hood not only helped conceal the headgear if it had not already received any type of winter covering, but also afforded protection to the back of the wearer's neck and to the ears. The trousers were also shapeless and were tucked into the boots.

Gebirgstruppen march in close formation across the snow. Without their white camouflage smocks these soldiers would have undoubtedly been vulnerable to enemy air attack. Close formation marching like this was commonly used by the Gebirsjäger, especially in arctic weather conditions where the soldiers would be able to stay in close proximity to each other, especially in low visibility.

Ski troops transport an injured comrade on a sled to a makeshift field hospital. Living and fighting in sub-zero temperatures was very difficult for the Germans, even for hardened veterans fighting their second winter in Russia. In a number of areas, in Northern Russia, wheeled transport was generally useless in the trackless wastes and forests, and often the most effective means of transport was the sled.

Gebirgs soldiers supported by animal draught advance along a road. A supply vehicle can be seen passing the column.

Mule drawn 1f.8 infantry carts of the 1.Gefa/rgs-Division can be seen crossing a stream. Note the reluctant bull attached to the cart. The 1.Gebirgs-Division fought on the southern flank of the Eastern Front, fighting at Kiev, Stalino, the Dnepr crossing, and Kharkov, before moving into the Caucasus during Operation Blau. After the defeat at Stalingrad, it spent time in Greece and Serbia before retreating to Austria, until it finally surrendered.

Weary and exhausted Gebirgstruppen during their withdrawal through southern Russia, in the late summer of 1943. After the defeat at Stalingrad, the 1 and 4 Gebirgs- Divisions were withdrawn, barely escaping the clutches of the Red tide. Both divisions halted at the Kuban bridgehead where they fought until the autumn of 1943 in mosquito-infested marshland.

Two photographs showing the terrible road conditions endured on the Eastern Front, in the autumn of 1943. Two vehicles and a motorcyclist from the 1.Gebirgs-Division struggle through the mire after a heavy downpour of rain. Roads in the Soviet Union were few, and cross-country travel often caused its own problems. Coupled with the sheer size of the country, the Russian weather offered the invaders considerably greater challenges than on any other front during the war.

Pack mule handlers rest with their animals. The vast distances in which these animals and their handlers had to travel can well be imagined. Typical Russian steppes comprised of nothing but vast expanses of flat terrain, stretching for as far as the eye could see. Due to the visible landmarks, units were often unable to determine their exact location.

A long column of mule pack handlers with their animals trudge along a muddy road, passing stationary vehicles and a motorcycle that has obviously developed a mechanical problem. The mules were versatile and sturdy animals and often endured painful long marches with little provision. Note the special canvas tarpaulin covers to protect the pack-loads.

Chapter Four. Last Months (1944 - 1945)

In the last months of the war, German forces continued receding across a scarred and devastated wasteland. On both the Western and Eastern Fronts, the last agonising moments of the war were played out. On the Western Front, in order to try and help stabilize the deteriorating situation, the Gebirsjäger troops were deployed following the failure of the Ardennes offensive. Known as Operation 'Northwind' elements of 6.SS.Gebirgs-Division 'Nord' were thrust into the line in a drastic attempt to hold back the advancing Allies in the Vosges region. Though these Waffen-SS mountain troopers were now well-seasoned veterans from the Eastern Front, the offensive was doomed from the start. Nonetheless, supported by the 2.Gebirgs-Division, the 6.SS.Gebirsg-Division 'Nord' pressed home its attacks and caused severe damage on a number of American units. Although the Americans were superior in both armour and infantry, they were masters at fighting in the surrounding pinewoods. The moun¬tain troops, Alpine skills unnerved the American troops and in some sectors reduced their fighting abilities. However, despite the superior tactics of the Gebirsjäger, the long exposure of battle, coupled with heavy losses, reduced combat efficiency of the mountain troops.

Despite their gradual deterioration, they continued to fight on, withdrawing steadily as British and American troops advanced towards the River Rhine. In the East too they fought tenaciously against the terrifying advance of the Red Army as its powerful force bore down on the River Oder, pushing back the last remnants of Hitler's exhausted units. The resistance of her once mighty armies were now collapsing amid the ruins of the Reich. Most of the so called Waffen-SS crack divi¬sions were still embroiled in heavy fighting in Hungary and were unable to be released, in order to plug the massive gaps on the German front lines in the East. Many of the volunteers, spurred on by the worrying prospect of Russian occupa¬tion of Europe and certain death if captured, were determined to defend to the bitter end and try to hold back the Red Army advance.

In Hungary, the situation was dire. In order to try and help stall the mighty onslaught of the Soviet thrust to Budapest, the Gebirsjäger fought bitterly to protect the Hungarian oilfields. With skill and tenacity, the mountain troopers held their lines in a number of places, in spite of the overwhelming strength of the enemy. But, once again, dwindling reserves meant that they were unable to retain their meagre positions and reluctantly pushed back, with heavy loss in men and material.

Gebirsjäger rest on a mountainside. Behind them sits a captured bullet riddled bunker that suggests there has been signs of some significant fighting in the area. Both soldiers wear the Zeltbahn. The Zeltbahn was designed with a slit in the middle for the wearer's head and could be worn comfortably over the shoulders, hanging down to protect the army field service uniform and field equipment. When worn like this, the Zeltbahn was known by the troops as the Regenmantel or rain cape.

A Gebirsjäger MG34 machine gun squad on a mountainside during operations against Red Army forces. All the troops wear the Zeltbahn. When the wearer no longer required the use of the Zeltbahn, it was usually rolled up and fitted to the personal equipment with two leather straps. The Zeltbahn was also sometimes seen attached to the D rings of the 'Y' straps, or to the back of the leather belt.

Whilst a number of Gebirsjäger formations fought to almost to distinction across the wastelands of Hungary, during the third week of January 1945, the Russians began their great winter offensive. The principal objective was to crush the remaining German forces in Poland, East Prussia and the Baltic states. Along the Baltic, an all-out Russian assault had begun in earnest, with the sole intention to crush the remaining understrength German units that had once formed Army Group North. It was these heavy, sustained attacks that eventually restricted the German-held territory in the north-east to a few small pockets of land surrounding three ports: Libau, Kurland, Pillau in East Prussia and Danzig at the mouth of the River Vistula.

Here, along the Baltic, the German defenders attempted to stall the massive Russian push with the remaining weapons and men they had at their disposal. Every German soldier defending the area was aware of the significance if it was captured. Not only would the coastal garrisons be cut off and eventually destroyed, but also masses of civilian refugees would be prevented from escaping from those ports by sea. Hitler made it quite clear that all remaining forces, including the Gebirsjäger, were not to evacuate, but to stand and fight and wage an unprecedented battle of attrition.

In southwest Poland, situated on the River Oder, the strategic town of Breslau had been turned into a fortress and defended by various Volkssturm, Hitlerjugend, Waffen-SS, Gebirsjäger and various formations from the 269.lnfantry-Division. During mid-February 1945, the German units put up a staunch defence with every available weapon that they could muster. As the battle ensued, both German soldiers and civilians were cut to pieces by Russian attacks. During these viscous battles, which endured until May 1945, there were many acts of courageous fighting. By the first week of March, Russian infantry had driven back the defenders into the inner city and were pulverising it, street by street. When defence of Breslau finally capitulated, almost 60,000 Russian soldiers were killed or wounded trying to the capture the town, with some 29,000 German military and civilian casualties.

With every defeat and withdrawal came ever-increasing pressure on the commanders to exert harsher discipline on their weary men. The thought of fighting on German soil for the first time resulted in mixed feelings among the soldiers. Although the defence of the Reich automatically stirred emotional feel¬ings to fight for their land, not all soldiers felt the same way. More and more young conscripts were showing signs that they did not want to die for a lost cause. Conditions on the Eastern Front were miserable, not only for the newest recruits, but also for battle-hardened soldiers who had survived many months of bitter conflict against the Red Army. The cold harsh weather during February and March prevented the soldiers digging trenches more than a metre down. But the main problems that confronted the German forces during this period were shortages of ammunition, fuel and vehicles. Some vehicles in a division could only be used in an emergency and battery fire was strictly prohibited without permission from the commanding officer. The daily ration, on average, per division was for two shells per gun.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com