RICHARD NATKIEL

ATLAS OF WORLD WAR II

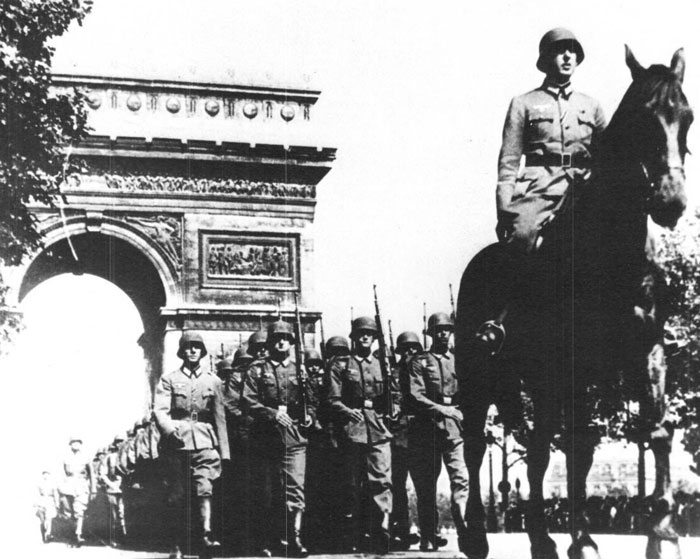

The conquered nation was divided into occupied and unoccupied zones. The Petain Government would rule the unoccupied zone from Vichy and collaborate closely with the Germans, to the revulsion of most Frenchmen. The 'Free French,' led by Charles de Gaulle, a young army officer and politician, repudiated the Vichy regime and departed for England, where de Gaulle announced that France would ultimately throw off the German oppressors.

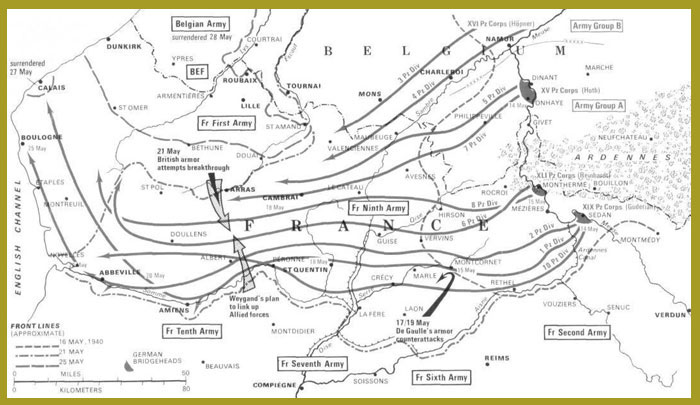

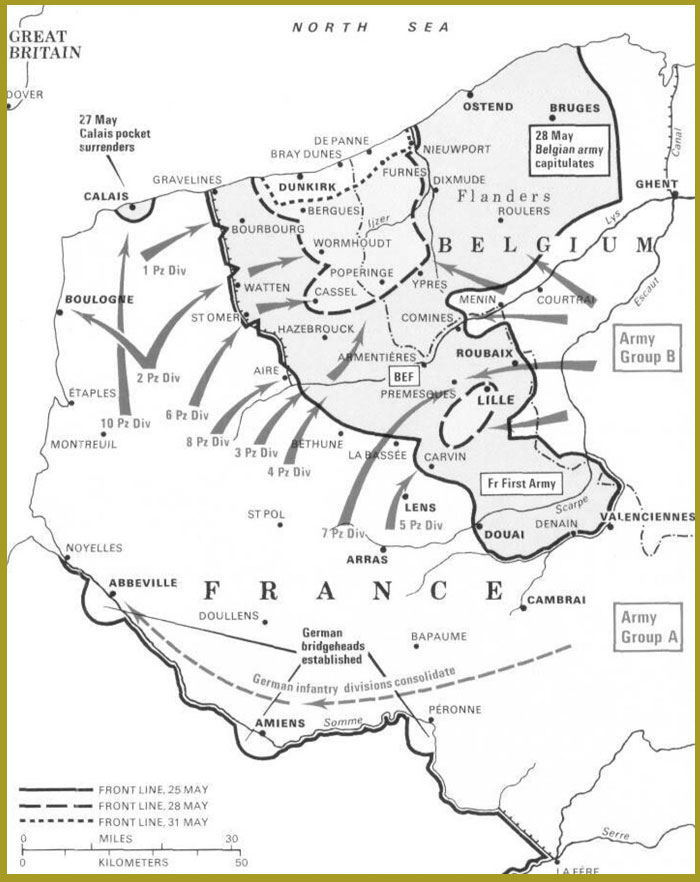

The Allied front line contracts as France and Belgium are overrun.

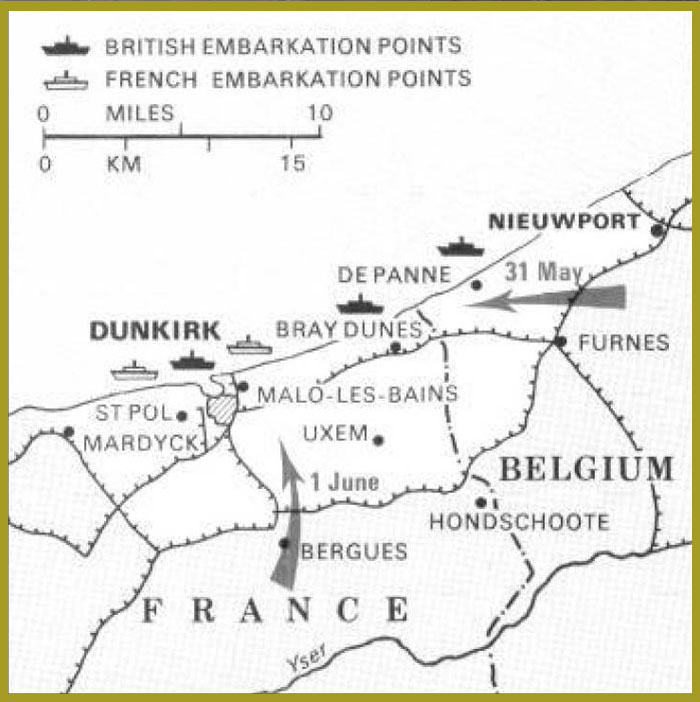

The Allies prepare to evacuate as the Germans advance.

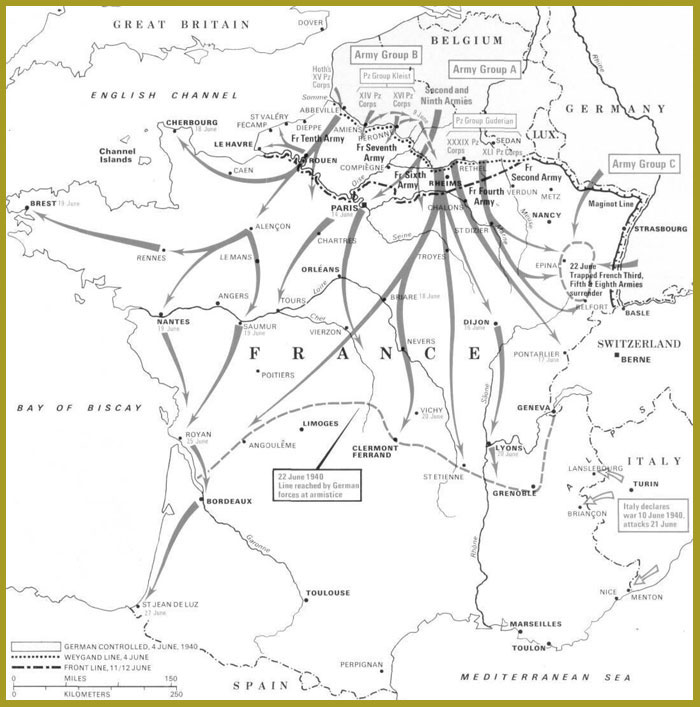

France divided under Nazi and Vichy rule.

The occupying forces move into Paris in June.

German vacillation and the spirited defense of Calais gave the Allies time to evacuate from Dunkirk.

A British soldier is hit by strafing Luftwaffe aircraft on the Dunkirk beach.

The British Expeditionary Force and their French allies await departure.

The aftermath of evacuation.

The German sweep southwards through France that resulted in the 22 June armistice. Note Italian incursions from the southeast.

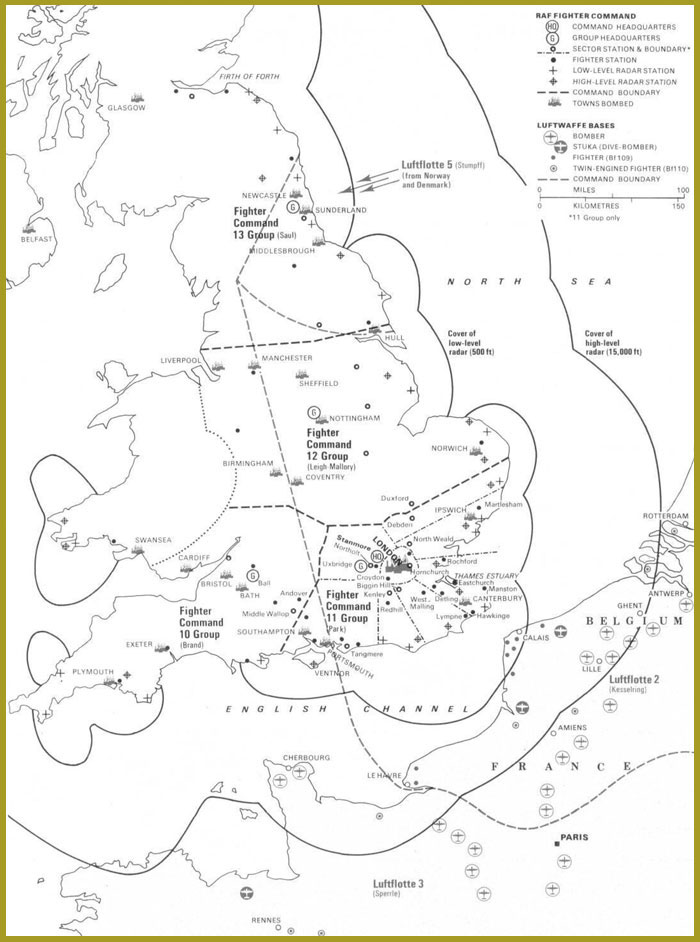

The Battle of Britain was fought in the air to prevent a seaborne invasion of the British Isles. The German invasion plan, code-named Operation Sealion, took shape when Britain failed to sue for peace, as Hitler had expected, after the fall of France. On 16 July 1940, German Armed Forces were advised that the Luftwaffe must defeat the RAF, so that Royal Navy ships would be unprotected if they tried to prevent a cross-Channel invasion. It was an ambitious project for the relatively small German Navy, but success would hinge upon air power, not sea power.

There were only some 25 divisions on British home ground, widely scattered and ill supplied with equipment and transport. The RAF alone could gain the time necessary for the army to re-equip after Dunkirk, and hold off the Germans until stormy fall weather made it impossible to launch Operation Sealion. The air arm was well led by Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding, who made the most of his relatively small but skillful force. The RAF had the advantage of a good radar system, which the Germans unwisely neglected to destroy, and profited also from the German High Command's decision to concentrate on the cities rather than airfields.

All-out Luftwaffe attacks did not begin until 13 August, which gave Britain time to make good some of the losses incurred at Dunkirk and to train additional pilots. On 7 September London became the main German target, relieving pressure on British airfields which had suffered in earlier bombings. RAF pilots who were shot down unwounded could, and often did, return to combat on the same day, while German pilots were captured. The short-range Messerschmitt Bf 109 could stay over England only briefly if it were to return to its base in France, which helped cancel out the German superiority in numbers of planes and pilots.

The stage is set for the Battle of Britain, 1940.

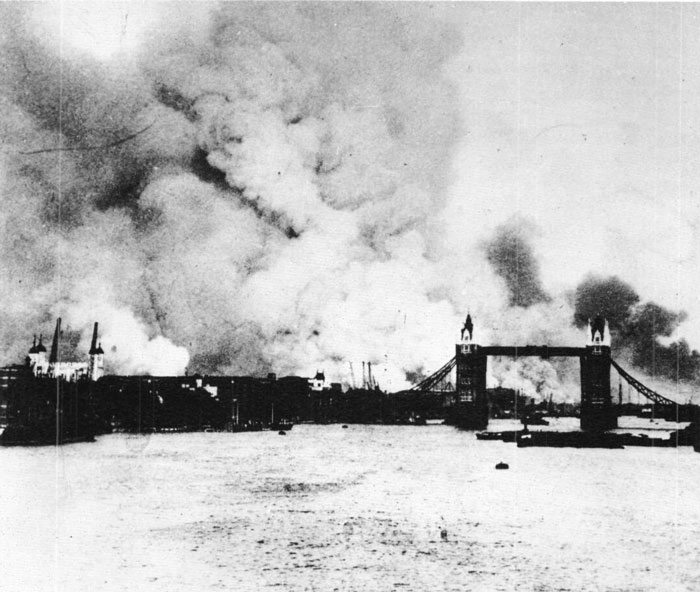

London's dockland burns after one of the first major bombing raids on the capital, 7 September 1940.

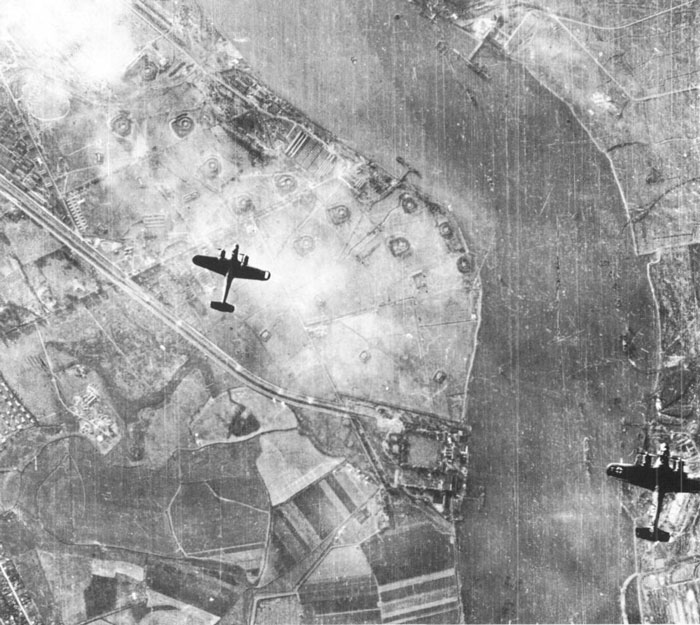

Two Luftwaffe Dormer Do 17 bombers over the River Thames, September 1940.

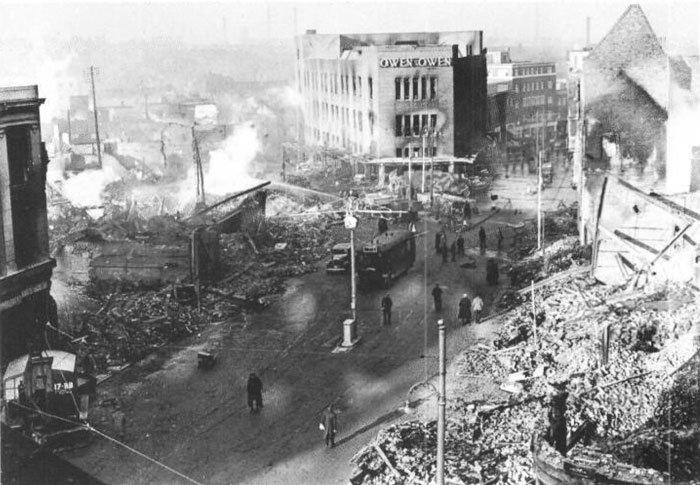

Aftermath of heavy night bombing in the Midlands city of Coventry two months later.

The Battle of Britain raged in the skies for almost two months, while a German fleet of barges and steamers awaited the signal to depart the Channel ports for the British coast. By mid September, the invasion date had already been put off three times, and Hitler had to concede that the Luftwaffe had failed in its mission. Sporadic German bombing would continue until well into 1941, but Operation Sealion was 'postponed' indefinitely.

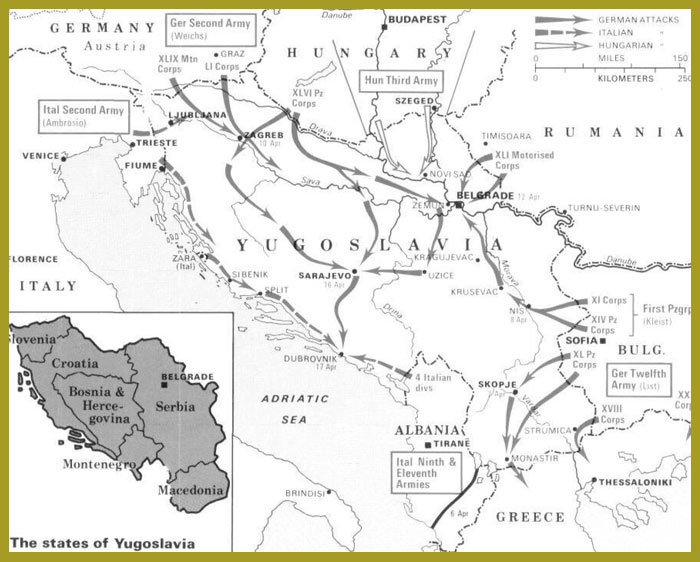

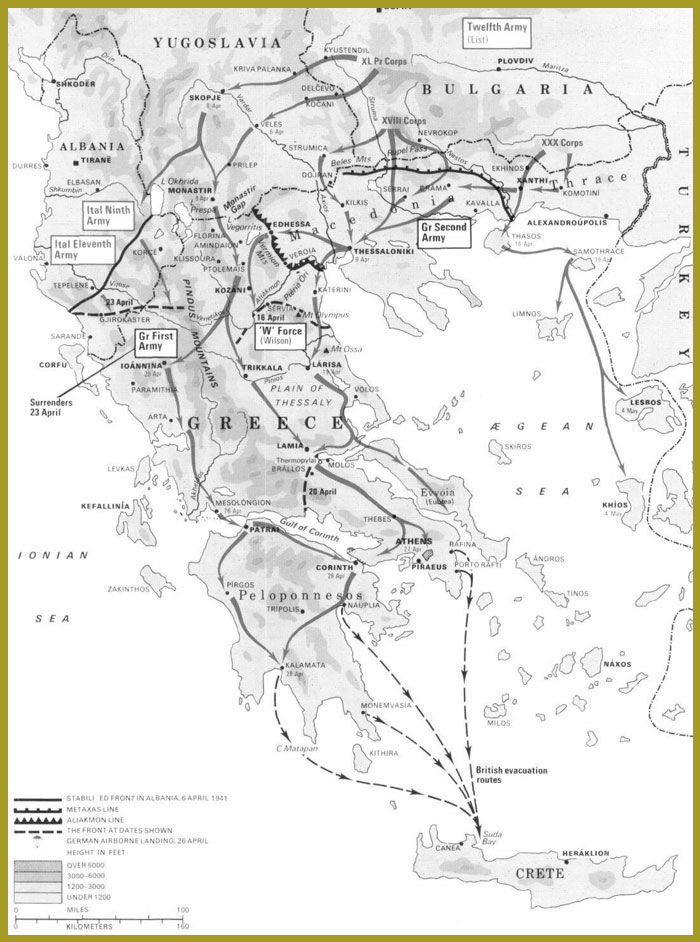

On 6 April 1941, the Germans moved to extend their influence in the Balkans by an attack on Yugoslavia, whose Regent, Prince Paul, had been coerced into signing the Tripartite Pact on 25 March. As a result, he was deposed by a Serbian coalition that placed King Peter on the throne in a government that would last only a matter of days. Hitler ordered 33 divisions into Yugoslavia, and heavy air raids struck Belgrade in a new display of blitzkrieg. At the same time, the Yugoslav Air Force was knocked out before it could come to the nation's defense.

The German plan called for an incursion from Bulgaria by the Twelfth Army, which would aim south toward Skopje and Monastir to prevent Greek assistance to the Yugoslavs. Thence they would move into Greece itself, for the invasion that had been planned since the previous year. Two days later, General Paul von Kleist would lead his First Panzer Group toward Nis and Belgrade, where it would be joined by the Second Army and other units that included Italians, Hungarians and Germans.

The plan worked smoothly, and there was little resistance to any of the attacks mounted between 6 and 17 April, when an armistice was agreed after King Peter left the country. Internal dissension among the various Yugoslavian states was a help to the Germans, who lost fewer than 200 men in the entire campaign. Another factor in their favor was the defenders' use of an ineffectual cordon deployment that was no match for the strength and numbers thrown against them. German air superiority completed the case against Yugoslavian autonomy.

Yugoslavia falls in the face of pressure from Germany, Hungary' and Italy, April 1941.

The overthrow of Yugoslavia's Regency Government on 21 March 1941 changed Hitler's scenario for southeastern Europe. Prior to that, he had planned to assist his Italian allies in their ill-starred Greek campaign by persuading Bulgaria and Yugoslavia to allow his troops free passage into Greece. Now he would have to invade both Yugoslavia and Greece, where the British were landing over 50,000 men in an attempt to enforce their 1939 guarantee of Greek independence.

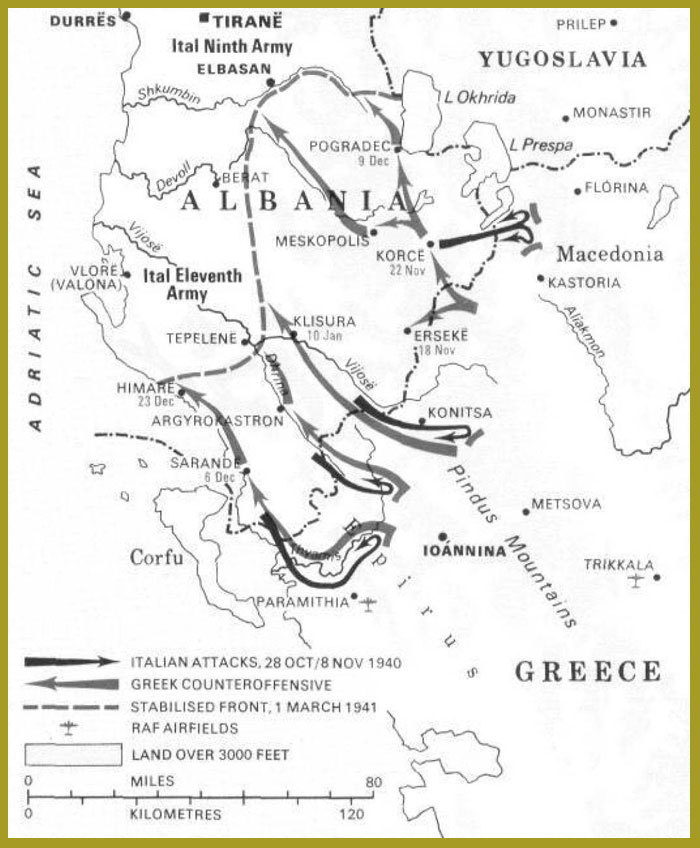

Mussolini's forces had crossed the Greek frontier into Albania on 28 October 1940, but their fortunes had been going downhill since November. The Greeks mobilized rapidly and pushed the Italians back until half of Albania was recovered, with British assistance, by March of 1941. The prospect of his ally's defeat, coupled with British proximity to the oil fields of Rumania, motivated Hitler to send three full army corps, with a strong armor component, into Greece. The attack was launched on 6 April, simultaneously with the invasion of Yugoslavia.

Allied forces in Greece included seven Greek divisions - none of them strong - less than two divisions from Australia and New Zealand, and a British armored brigade, as well as the forces deployed in Albania. British leaders wanted to base their defense on the Aliakmon Line, where topography favored them, with sufficient forces to close the Monastir Gap. But the Greek Commander in Chief held out for a futile attempt to protect Greek Macedonia, which drew off much-needed troops to the less-defensible Metaxas Line. The Germans seized their chance to destroy this line in direct attacks and push other troops through the Monastir Gap to outflank the Allied defense lines.

By 10 April the German offensive was in high gear and rolling over the Aliakmon Line, which had to be evacuated. A week later, General Archibald Wavell declined to send any more British reinforcements from Egypt - a sure sign that the fight for Greece was being abandoned. Some 43,000 men were evacuated to Crete before the Germans closed the last Peloponnesian port at Kalamata; 11,000 others were left behind.

Italian attacks and Greek counteroffensives, winter 1940-41.

The British evacuate the Greek mainland as Axis forces thrust southwards.

German mountain infantry march through the township of Lamia in April 1941.

A surfaced German U-boat immediately prior to its sinking by US Navy bombers southwest of Ascension Island, November 1943.

Battle of the Atlantic 1939-42

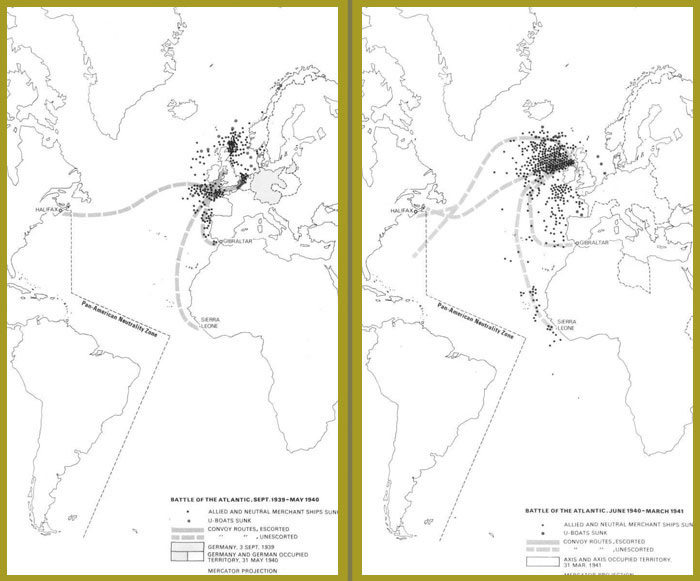

The memory of German submarine success in World War I led the British to introduce a convoy system as soon as hostilities began. The immediate threat was less than British leaders imagined, because submarine construction had not been given high priority in the German rearmament program, and Hitler was reluctant to antagonize neutral nations by unrestricted submarine warfare. This was fortunate for the British in the early months of the war, because they lacked sufficient escort vessels. Many ships sailed independently, and others were convoyed only partway on their voyages.

In June 1940 the U-boat threat became more pressing. The fall of France entailed the loss of support from the French Fleet even as British naval responsibility increased with Italian participation in the war. Germany's position was strengthened by the acquisition of bases in western France and Norway for their long-range reconnaissance support planes and U-boats. And German submarines, if relatively few in number, had several technical advantages. Their intelligence was superior to that of the British due to effective code-breaking by the German signals service. British Asdic equipment could detect only submerged submarines; those on the surface were easily overlooked at night or until they approached within striking distance of a convoy. Radar was not sophisticated, and British patrol aircraft were in very short supply.

Early developments in the Battle of the Atlantic. Below.

USS Spencer closes on a U-boat off the east coast of America.

As a result, the Battle of the Atlantic was not one of ships alone. It involved technology, tactics, intelligence, airpower and industrial competition. The Germans made full use of their advantages in the second half of 1940 (known to German submariners as 'the happy time'). U-boat 'wolf-packs' made concerted attacks on convoys to swamp their escorts, and numerous commanders won renown for the speed and success of their missions.

By March 1941 this picture was changing. Many U-boats had been destroyed, and replacement construction was not keeping pace. The British provided stronger escorts and made use of rapidly developing radar capabilities to frustrate German plans. Three of the best German U-boat commanders were killed that March, and Churchill formed the effective Battle of the Atlantic Committee to co-ordinate British efforts in every sphere of the struggle. The remainder of 1941 proved that a balance had been struck: German U-boats tripled in number between March and November, but shipping losses in November were the lowest of the war to that date. US assistance in both convoy duty and supplies helped improve the British position, as did intelligence breakthroughs.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com