RICHARD NATKIEL

ATLAS OF WORLD WAR II

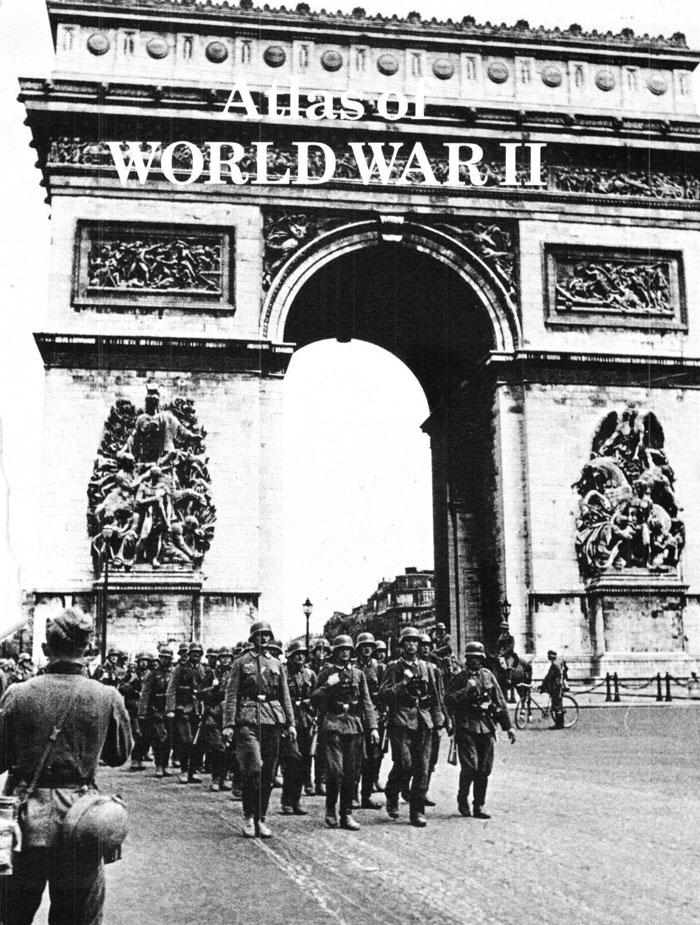

Occupying German troops march past the Arc de Triomphe, Paris, 1940.

It has often been stated that World War II was part of a European Civil War that began in 1914 at the start of World War I. This is partly true. In Europe, at least, the two world wars were the two hideous halves of the Anglo-German controversy that was at the heart of both conflicts. The question posed was: would Britain be able, or willing, to maintain her vast Empire in the face of German hegemony on the continent of Europe? The answer to that question never came. Britain, in seeking to thwart German interests on the Continent, eventually lost her whole Empire in the attempt -an empire that between the wars encompassed a quarter of the earth's surface and an equal proportion of its population. Put into that context, both world wars were dangerous for Britain to fight, jeopardizing the very existence of the Empire and inevitably weakening the mother country to the point that she could not maintain her world position at the end of the conflicts.

Italian troops on the Eastern Front, 1942

From Germany's point of view, the wars were not only dangerous in that they finally ruined virtually every town and city, devastated the countryside and dismembered the nation; they were irrelevant. In 1890 Germany was in a position from which, within a generation, she would economically dominate the whole of Europe. Inevitably, with that economic hegemony, political hegemony would soon follow, if not even precede. By 1910 the process was well in train; had no one done anything to stop her, Germany would have achieved the Kaiser's dreams without war by the mid 1920s. The collapse of Imperial Germany in 1918, followed by temporary occupation, inflation and national humiliation, set Germany back only a few years. Despite the disasters of World War I and its aftermath, Germany was quickly recovering her old position - roughly that of 1910 - by the time Hitler took power in 1933. By 1938 German power in Europe was greater than ever before, and Britain had to face the old question once again. Could she condone German political dominance of the Continent?

US Marines at Iwo Jima plot the position of a Japanese machine gun post, February 1945.

In 1938 some Conservatives, like Chamberlain and Halifax, recognized the threat and were tacitly willing to maintain the Imperial status quo and condone Hitler. Other Tories, like Churchill and the Labour and Liberal Parties, wanted to challenge Germany again. Had Hitler been a bit more discreet and less hurried, perhaps a bit less flamboyant and virulently anti-Semitic, Chamberlain's policy might have succeeded. Germany would have extended her power in Europe and the Empire would have been maintained. But that was to ask the impossible, to wish that Hitler were someone other than Hitler. The result - humiliation of Britain's policy when Czechoslovakia was overrun in March 1939 - forced even Chamberlain's hand, and the stage was set for round two of the European Civil War.

Dunkirk, scene of an ignominious retreat by Allied forces thai signaled the Fall of France.

World War II in Europe was very like a Greek tragedy, wherein the elements of disaster are present before the play begins, and the tragedy is writ all the larger because of the disaster's inevitability. The story of the war, told through the maps of Richard Natkiel in this volume, are signposts for the historian of human folly. In the end, Germany and Italy were destroyed, along with much of Europe. With the devastation came the inevitable collapse of both the impoverished British Empire and centuries of European hegemony in the world. A broader look from the perspective of the 1980s would indicate a further irony. Despite Germany's loss of part of its Polish and Russian territory and its division into two countries, not to mention the separation of Austria from the Reich and the semipermanent occupation of Berlin, the German economic advance was only delayed, not permanently stopped. The Federal Republic is clearly the strongest economy in Western Europe today and the fourth strongest in the world. The German Democratic Republic rates twelfth on this basis. Together their economies are roughly as strong as that of the Soviet Union, and their political reunification is now less of a dream, more of a reality toward which Germans on both sides of the Iron Curtain are striving. One day, probably within the next two decades, a form of unification may take place, and when it does, German power on the Continent will be greater than ever before. No wonder the Soviets and many Western Europeans view this prospect with fear and cynicism. What had the world wars been for? For what ideals had the blood of tens of millions been spilt?

The successful Russian defense of Stalingrad was a major setback to German war plans.

The irony of World War II becomes even clearer when one views briefly its second half, the struggle between Japan and the United States for control of the Pacific. The question facing American Presidents from Theodore Roosevelt to Franklin Roosevelt had been: could the United states maintain its security and trade routes in the Pacific in the face of an increasingly powerful Japanese Navy and economy? For decades the question was begged, until the Japanese took matters into their own hands at Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, Vietnam and Malaya in 1941. The ensuing tragedy, as inevitable in the Pacific as was its counterpart in Europe, became obvious almost from the outset. Millions died in vain; Japan itself was devastated by fire and atomic bombs, and eventually conceded defeat.

Japanese tanks pass a wrecked British ambulance in Burma, 1942.

From a forty-year perspective, what was the point of the Pacific War? Japan has the third largest economy in the world and by far the largest in Asia. In recent years the United States has actually encouraged Japan to flex its political muscles, increase its armed forces and help the United States police the Western Pacific. It would seem that this conflict was as tragically futile as the European Civil War.

The greatest disaster in the history of mankind to date was World War II. This atlas is a valuable reference work for those who feel it bears remembering. Clearly, this is the case, but the lessons of the war have been less clearly spelled out - to those who fought in it, who remember it, or who suffered from it, as well as to subsequent generations who were shaped by it and fascinated by its horrific drama. The exceptional maps of Richard Natkiel of The Economist, which punctuate this volume, can give only the outlines of the tragedy; they do not seek to give, nor can they give, the lessons to be learned.

It would seem that if anything useful is to be derived from studying World War II, it is this: avoid such conflicts at all costs. No nation can profit from them. This is certainly truer today than if these words had been written in 1945. The advances of science have made a future world conflict even less appetizing to those who are still mad enough to contemplate such a thing.

Perhaps the balance of the 20th century and the early years of the 21st will be very like the past 40 years: small conflicts, limited wars, brinkmanship, arms races and world tension - yes; general war, no. If our future takes this course, the period following World War II may be seen by historians of the 21st century as a time similar to the century following the Napoleonic Wars - one of growing world prosperity, which has indeed been apparent for some nations since 1945, many crises, but no all-out war. If that is our future, as it has been our recent past, the study of World War II will have been more than useful. It will have prepared the world psychologically to avoid world conflict at all cost. In that event, for the sake of a relatively stable, increasingly prosperous 'cold peace,' the 1939-45 conflict will not have been in vain. If war is the price for a bloodstained peace, those who will benefit are ourselves and future generations.

S L Mayer

German blitzkrieg (lightning war) tactics were expertly executed by their highly trained troops.

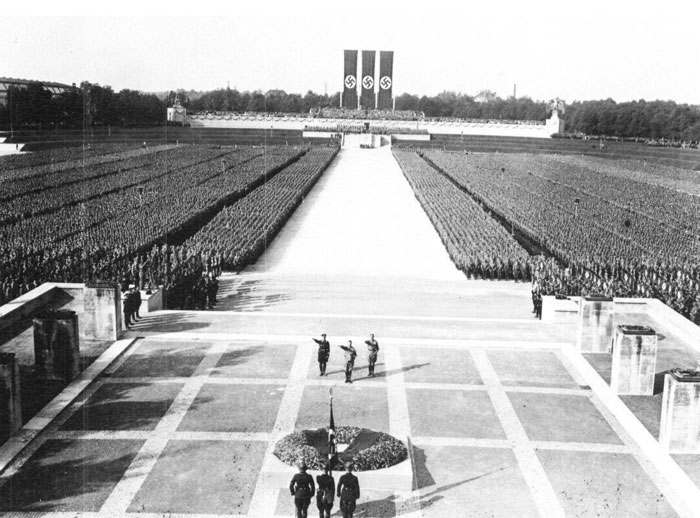

The German humiliation at Versailles was skillfully exploited by Adolf Hitler and his Nazis, who rode to power in 1933 on a tide of national resentment that they had channeled to their purpose. The territorial losses, economic hardships and affronts to German pride embodied in the Treaty of Versailles virtually guaranteed the conflict that escalated into World War II. As Marshal Foch had prophesied when the treaty was forced upon a prostrate Germany: 'This is not Peace. It is an Armistice for twenty years.'

Hitler's stormy career seemed to reach its zenith when he seized control of the German Government in March of 1933. In fact, it was only beginning. Hitler implemented a military build-up in defiance of the Versailles Treaty, which had limited German armed forces to an army of 100,000 and a small navy without armor or air force support. Groundwork was laid for a much larger army to be built up by conscription upon a highly trained professional base organized by General Hans von Seeckt. The prohibited tanks and planes were developed secretly, many in the Soviet Union, and future pilots were trained. Meanwhile, the Nazis continued to scapegoat the Jews and other minorities for the nation's problems; they established the first concentration camp at Dachau in the same year they came to power.

Germany's expansion by August 1939.

Detail showing the recently annexed Rhineland and Sudetenland.

Germany withdrew from the League of Nations, ana by 1935 Hitler could announce repudiation of the Treaty of Versailles. He told the world that the German Air Force had been re-created, and that the army would be strengthened to 300,000 through compulsory military service. The Western democracies, France and Britain, failed to make any meaningful protest, a weakness that encouraged Hitler's ambition to restore Germany to her 'rightful place' as Europe's most powerful nation.

Nazi Germany's first overt move beyond her borders was into the Rhine- land, which was reoccupied in 1936. This coup was achieved more through bravado than by superior force. Hitler's generals had counseled against it on account of the relative size of France's army, but the reoccupation was uncontested. The next step was to bring all Germans living outside the Reich into the 'Greater Germany.' Austria was annexed in March 1938, with only token protests from Britain and France. Even more ominous was Hitler's demand that Czechoslovakia turn over its western border - the Sudetenland - on ground that its three million German-speaking inhabitants were oppressed. The Nazis orchestrated a demand for annexation among the Sudeten Germans, and the Czechoslovakian Government prepared to muster its strong armed forces for resistance. Then British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain flew to Munich to confer with Hitler.

The Nuremberg Rally in 1934, with Adolf Hitler (center).

Chamberlain rationalized that the problem was one affecting Central Europe alone, and expressed reluctance to risk war on behalf of 'a far-off country of which we know little. France had to stand by its alliance with Britain, and the Czechoslovakian democracy was isolated in a rising sea of German expansionism. The Sudetenland, with its vital frontier defenses, was handed over. Far from securing 'peace in our time,' as Neville Chamberlain had promised after Munich, this concession opened the door to Nazi occupation of all Czechoslovakia in March 1939'.

Only at this point did the Western democracies grasp the true scope of Hitler's ambitions. Belatedly, they began to rearm after years of war-weary stasis. By now Hitler's forces were more than equal to theirs, and the Führer was looking eastward, where Poland's Danzig Corridor stood between him and East Prussia, the birthplace of German militarism.

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com