J.L. PETE MORGAN, TED A. THURMAN

AMERICAN MILITARY PATCH GUIDE (Army - Army Air Force - Marine Corps - Navy - Civil Air Patrol National Guard)

A Few Words About Patches In General And This Book In Particular

While the idea of using a shoulder sleeve insignia to identify a particular unit in the field had its' American start in the civil war, its' U.S. Army rebirth in the twentieth century was not without controversy. The story is told that in October of 1918 in France, the 81st "Wildcat" division began wearing an olive-drab circle with the black representation of a wildcat thereon. The design was to represent that the division had trained at Camp Jackson in South Carolina on the banks of Wildcat Creek. General Pershing felt that this was detrimental to uniform discipline and ordered that the patch be removed. After his staff studied the situation a bit further, it was found that the idea of each unit having a unique design on their uniform had a positive morale effect on the troops, and, trench warfare being what it was in WW I, the army needed all the positive effect it could find.

Being fairly smart (and, after all, he was the Commanding General), Pershing then ordered that all units should design a shoulder sleeve insignia and proceed to wear it on their uniforms. This gave a feeling to the individual that he was a member of a particular group and should take pride in the special accomplishments of that unit. Thus, began the army's headlong rush into insignia design. Soon, every unit had to have their own distinguishing marks on everything from the individual soldier to vehicles, equipment and in some cases, even buildings.

With the advent of WW II and the resulting explosive buildup of the military, shoulder sleeve insignia (SSI) designs proliferated. Hundreds of new designs appeared almost overnight. Designs were coming in from the units themselves, along with professional designs from Hollywood and New York. An entire industry sprang up almost overnight of designers, embroiderers, distributors and of course, collectors.

The purpose of this book is to provide a military reference source concentrating primarily on U.S. Army designs where most shoulder sleeve insignia originated. However, we have incorporated some of the most popular U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps designs that will be encountered. Keep in mind that in 1947 with the advent of the realignment of the armed services, several major changes occurred. The U.S. Air Force was created and separated from Army control to become an independent entity and the U.S. Marine Corps ceased wearing patches on uniforms.

Future volumes will portray the U.S. Air Force patches. We have included a section in this book to illustrate some of the "Unoffically Authorized" patches prevelent in the U.S. Marine Corps today.

There are many unofficial and variant designs in this book. It is simply because these patches are present today and will undoubtedly be encountered. We have made no distinction between "original and "reproduction" designs. This is an ongoing debate best left to those who revel in it.

With certain exceptions, the patches pictured in this book are from the author's collection. We hope that you gain as much enjoyment from the hobby as we have. GOOD HUNTING!

Patch Production Through The Years

Methods of construction and material used in making patches have been extremely varied over the years. From the most basic techniques to the highly sophisticated computer operations, the goal has always been to produce a design that someone can wear with pride and purpose.

Illustration #1

Illustration #2

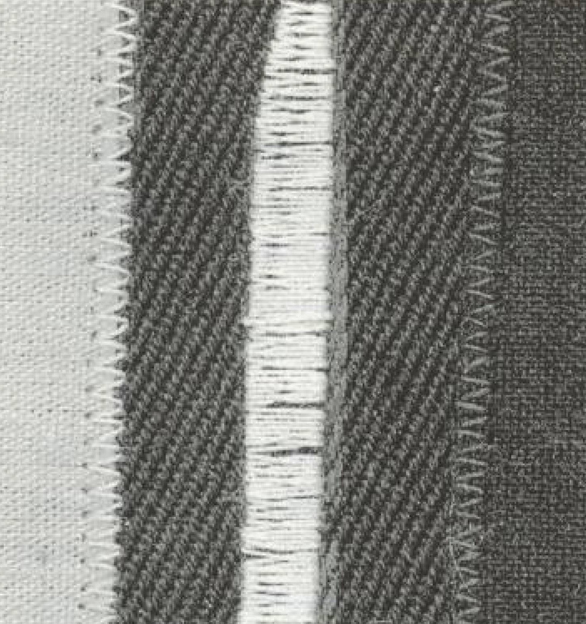

Originally, appliques were simply colored bits of cloth sewn together to make a design that met the need, (illustration #1). This led to the designs being embroidered on bits of uniform cloth. First by hand, (illustration #2) and later, with the development of machines, mass production became the norm.

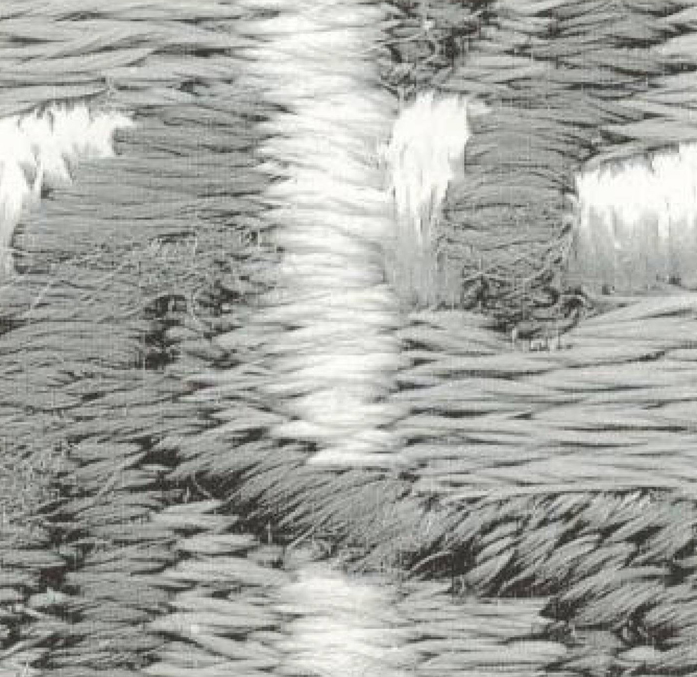

Early patches were made by machine with the design drawn on the fabric and the maker simply followed the drawing using a single needle. This is a crude method, and takes a skilled operator to produce an accurate design. This is commonly seen on in-country made Vietnam era patches (illustration #3)

Illustration #3

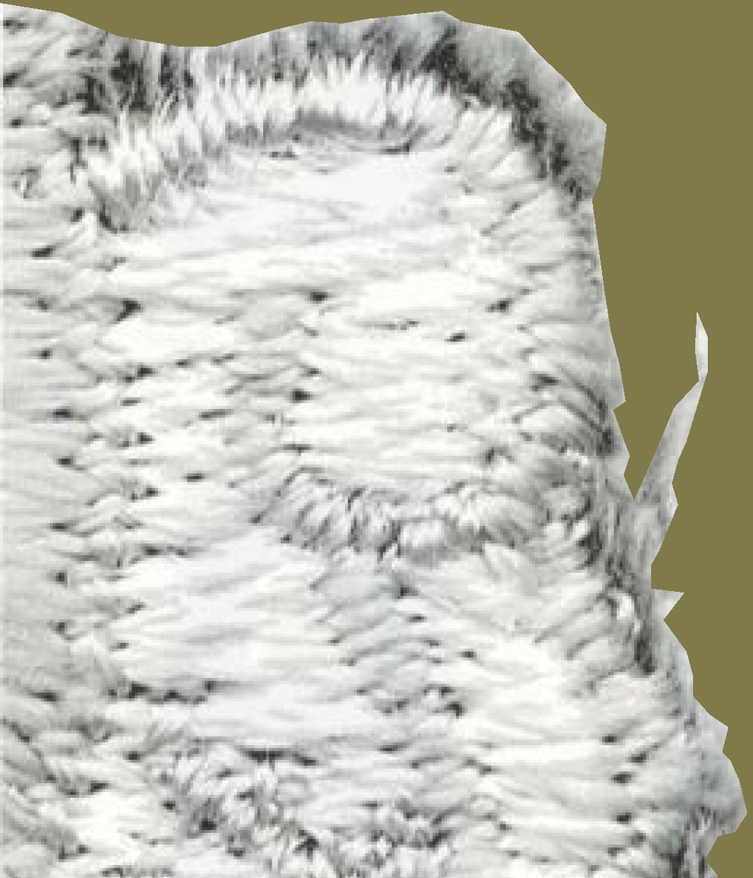

In the beginning, the most popular fabrics used were usually old bits of uniform on which the design was embroidered. Then, the design was cut out and stitched on the soldier's uniform. The development of the Schiffli machine in the late 19th century permitted the use of bolts or rolls of base fabric with as many as 360 needles embroidering as one. By the time of WW II, the Schiffli stitch had become the standard method by which most all U.S. military patches were produced. Because the machine was developed in Switzerland, this is sometimes referred to as "Swiss" embroidery. The bobbins are shaped like double-ended boats, hence, the term "Schiffli" (German: "Little Boat"). An example of the schiffli stitch is shown in illustration #4.

Illustration #4

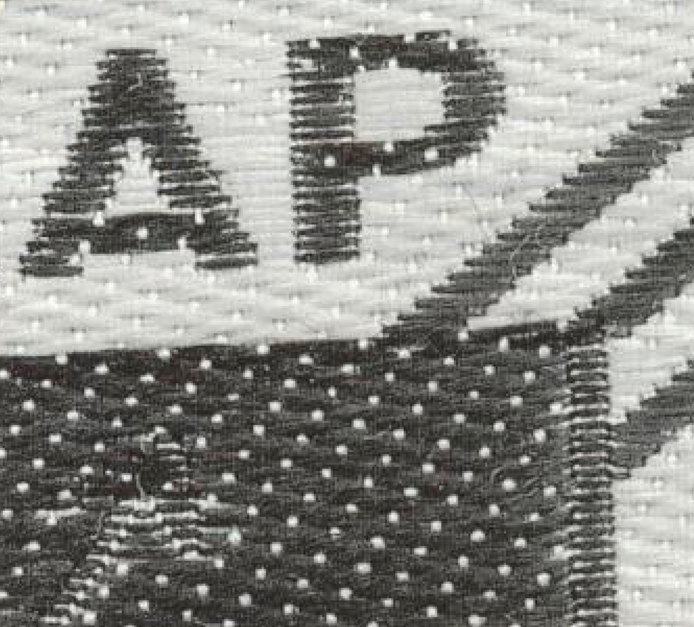

Another 19th century invention that was used to produce patches in large volume was the Jacquard weaving machine. This method of weaving was developed in France and employed a series of punched cards which permitted shuttles to move in a predetermined pattern to produce the design. The designs are made in one long ribbon and then cut from the strip as needed. This method is commonly used today to make clothing labels, ribbons and fine silk fabrics. A foremost producer of WW II German insignia using this method was the firm Bandfabrik Ewald Vorsteher. Today, in the world of insignia, the term "BEVo" is synonymous with this type of construction (illustration #5).

Illustration #5

With the rise in computer technology, patches are produced today in greater quantity and accuracy than ever before. The small machines can produce from one to twenty pieces at a time using multiple heads which eliminates the necessity of rethreading the needles for color changes. By using computers, it is possible to have registration of color and accuracy of design repeated in every patch in a production run (illustration #6).

Illustration #6

There are several methods used to finish the edges of patches to prevent the embroidery from unraveling. If the patch is cut from felt, there is normally no finishing and the edges are left raw. In the single needle type, it is common for the stitch to continue around the perimeter of the patch (illustration #7). The same is true of hand stitched designs.

Illustration #7

For schiflli made patches, it is normal for the direction of the perimeter stitch to simply be turned perpendicular to the main body stitch, (illustration #8) This would in effect lock in the stitches and prevent raveling. The entire patch design would then be cut from the main bolt of fabric and the process was completed. This is called a "cut" edge.

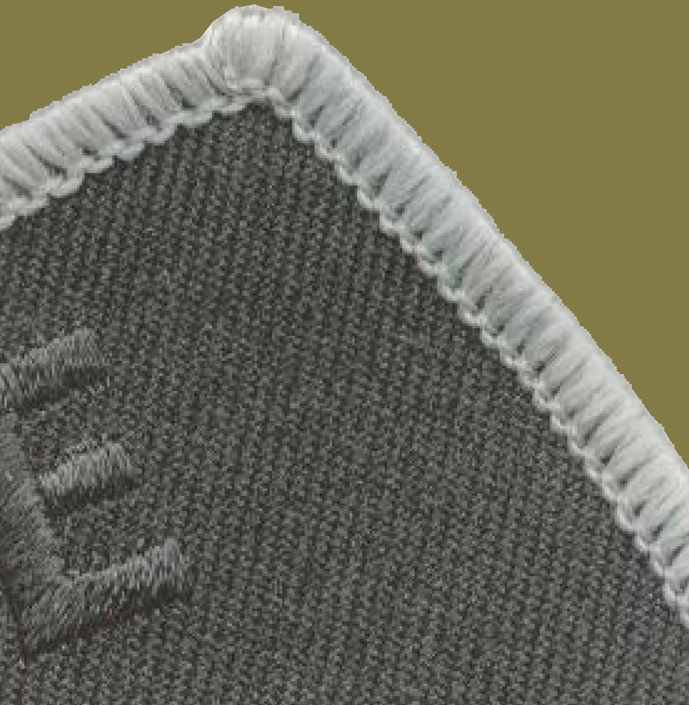

In the 1950's, The Merrow Sewing Machine Company developed a machine that would make a heavy overlock stitch around the outer perimeter of a patch. This stitch would produce an edge that would not unravel despite rough handling (illustration #9). This "merrowing" has become the standard method of finishing edges and is seen on almost all military patches made since the mid-1960's.

Illustration #8

Base fabrics upon which the embroidery is done have also changed during the years. Originally, natural fibers were used - cotton, wool, and linen. This continued until the late 1930s' and the development of man-made fibers. At this point, it became less expensive to use newly developed polyesters or a blend instead of pure natural products. Later, many manufacturers came to use a blended polyester base because of the advantages of being colorfast and having minimal shrinkage.

This is also true of the colored thread used to make the design. In the current market, it is very difficult to find patches being embroidered with anything except a blended polyester thread. Many attempts have been made to try to determine the age of a patch through the types of manufacture, colors of thread used in the bobbin and fiber content. Other tests used are black light, burn tests, smell and taste tests. None of these are absolutely accurate in dating the manufacture of a patch. Collectors should be as knowledgeable as possible regarding the methods of manufacture and construction of patches and make their collecting decisions accordingly.

Illustration #9

During the Vietnam War, the army changed their field uniform from the familiar OD fatigue uniform that had been standard since WWII to the now familiar Battle Dress Utility (BDU) camouflaged field uniform. On the new uniform, the brightly colored unit patches tended to defeat the camouflage effect desired. It was then decided to make all patches in two fashions. One in the standard colors and another for wear only on the new BDU's. The new patches were in shades of black and olive green in order to blend with the uniform. Although the colors are different, the methods of construction are the same as other patches.

Down through the years since knights painted their crests on their shields to identify themselves to friend and foe alike, man has sought to gain recognition not only as to who they are, but also as to what they are. Thus has come the idea of using colored bits of cloth and metal worn on clothing not only as personal identification but also to indicate the quality of his service in whatever endeavor he has embraced. The shoulder patch is a perfect embodiment of this need. It is little wonder that this small item has proven its value in filling a basic human need. If you are a collector, I hope that you have as much enjoyment as I have had over the last fifty years. Happy Collecting!

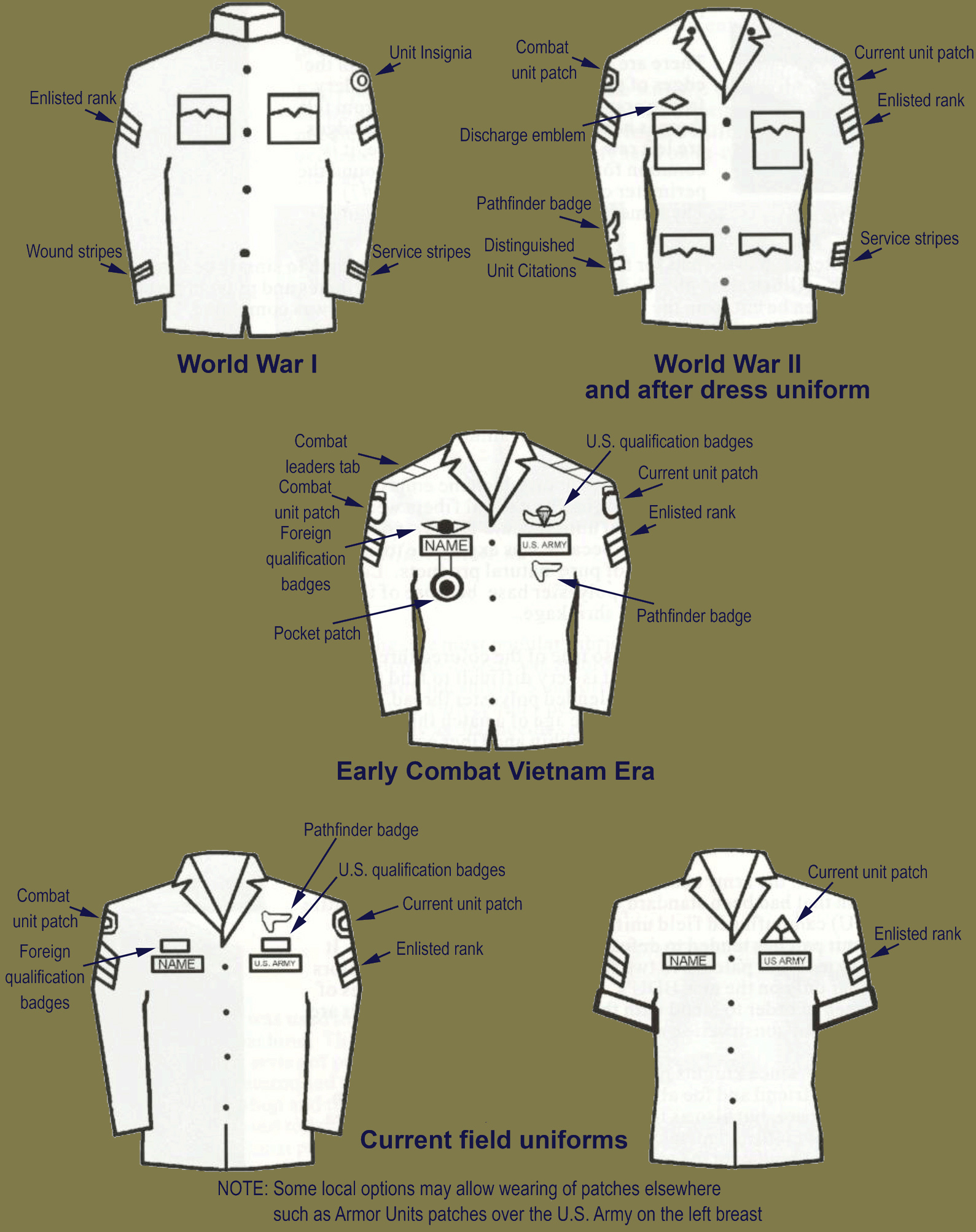

How Army Patches & Shoulder Sleeve insignia are worn

1st ARMY GROUP |  6th ARMY GROUP |  12th ARMY GROUP |  15th ARMY GROUP |

We have much more interesting information on this site.

Click MENU to check it out!

∎ cartalana.com© 2009-2025 ∎ mailto: cartalana@cartalana.com